The Treaty was signed in 1840 by representatives of the British Crown and more than 500 Māori chiefs. It symbolises the unique relationship between the peoples of this nation - a relationship that continues to evolve today.

1200s-1700s

THE PEOPLE OF THIS LAND

During this time period, Māori live in small, self-governing iwi (tribes) around New Zealand. They are descended from Polynesian navigators who arrived here in the late 1200s.

Māori are tangata whenua - the 'people of this land'.

Tairua fishing lure. This fishing lure made from tropical black-lipped pearl shell (Pinctada margaritifera) was found in a 1964 archaeological excavation at Tairua on the Coromandel Peninsula. The lure is highly significant because it was made in East Polynesia and brought here, on a waka, with the Polynesian settlers of Aotearoa. AU1785

13 December 1642

ABEL TASMAN A BRIEF ENCOUNTER

Dutchman Abel Tasman becomes the first European explorer to discover New Zealand. He anchors in Golden Bay on the northern coast of the South Island but leaves without going ashore following a bloody encounter with Māori.

Soon afterwards, a Dutch map-maker gives the country the name 'Nieuw Zeeland'.

Dutch merchants hoped a vast southern continent existed in the Pacific, and that it would offer new opportunities for trade.

October 1769

CAPTAIN COOK MAKES LANDFALL

English explorer James Cook arrives in New Zealand on the ship Endeavour, on the first of three voyages of discovery. He charts New Zealand and provides Europe with its first substantial knowledge of the Māori people. Cook estimates the Māori population at 100,000 - a figure modern historians believe is accurate.

Tupaia the Tahitian navigator plays a crucial role as interpreter, and is welcomed by some Māori as a tohunga (priest, navigator, scholar).

Cook's discoveries help forge New Zealand's later links with Britain. But, for Māori in New Zealand, the visit is a brief interlude in the normal course of life.

Early 1800s

OPPORTUNITIES FOR TRADE

Sealers, whalers and missionaries are some of the first to settle in New Zealand, and Māori are quick to see the benefits of trade.

The Ngāpuhi chief Te Pahi, a senior leader from the Bay of Islands, is the first influential Māori leader to have significant contact with British officials. In 1805-1806 he spends three months in Sydney, Australia as a guest of Governor Philip King. King wants protection for British whaling crews in New Zealand, whereas Te Pahi is eager to learn about new technology, English farming techniques, and British laws. His visit helps to convince colonial officials that partnerships with Māori will benefit both sides.

Te Pahi also meets missionary Samuel Marsden and impresses him with his ‘clear, strong and comprehensive mind’. Marsden begins planning a mission in the Bay of Islands.

1818-1840

THE MUSKET WARS

The use of European muskets changes the face of warfare between Māori tribes.

Māori are quick to see the advantages these long-barrelled guns give them in combat. By the 1920s, an arms race is in full swing. The Northland tribe Ngāpuhi is the first to acquire a stockpile of hundreds of weapons. Each gun costs as much as 15 pigs - a huge drain on tribal resources.

European diseases are the main cause of death among Māori, but thousands also die in the Musket Wars. Many more are enslaved by enemy tribes, or flee their traditional lands, vacating large areas for potential Pākehā settlement.

1834

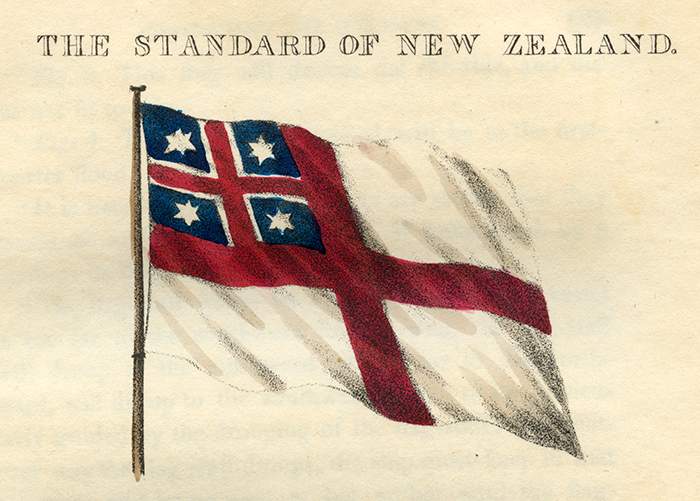

THE COUNTRY'S FIRST FLAG

Māori chiefs select a flag - a legal requirement for any New Zealand-owned ships which are now trading overseas.

The United Tribes flag is the first distinctly New Zealand flag. It is not, however, a truly 'national' one. Each iwi (tribe) is self-governing and there is no sense of a united country.

United Tribes' flag as published in the 1855 book 'An account of New Zealand and of the formation and progress of the Church Missionary Society's mission in the northern island' by Missionary William Yate.

28 October 1835

THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE

Britain's representative, James Busby, calls a meeting of predominantly northern Māori chiefs and encourages them to sign a 'Declaration of Independence'.

The document asserts the independence of Niu Tiremi (New Zealand) but also calls on King William IV to be a 'parent' of this 'infant state'.

Busby's goal is to prevent the French from establishing their own colony - a very real threat. The signing of the declaration takes Māori a step closer to a binding relationship with Britain.

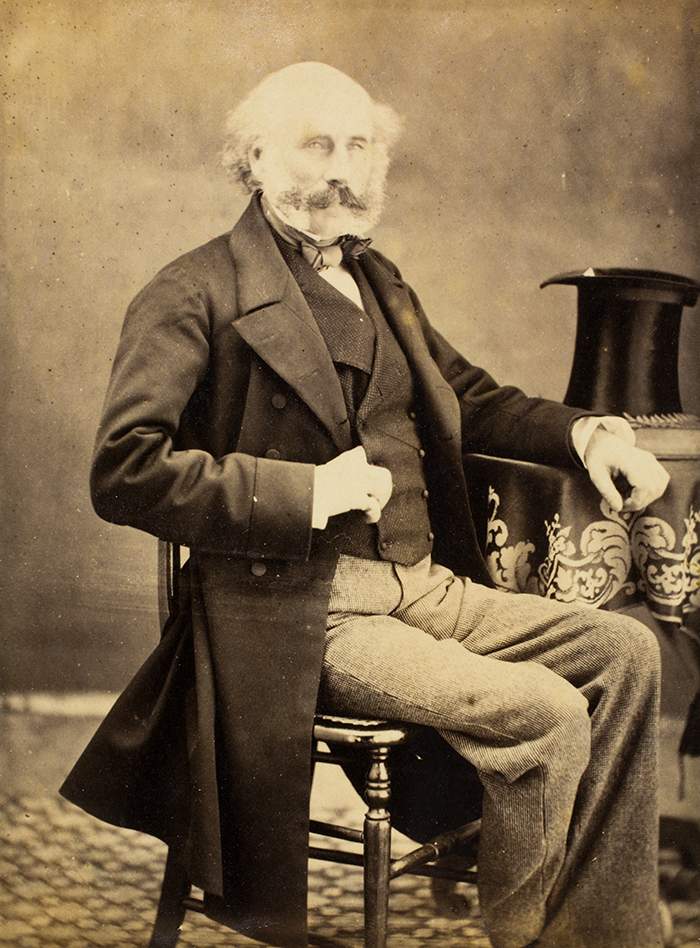

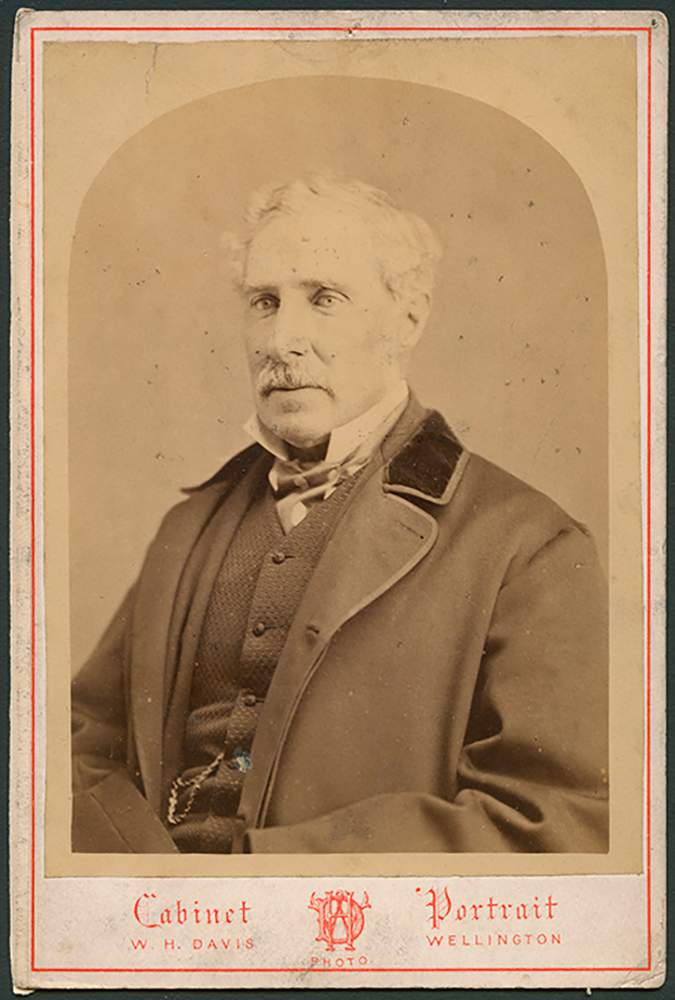

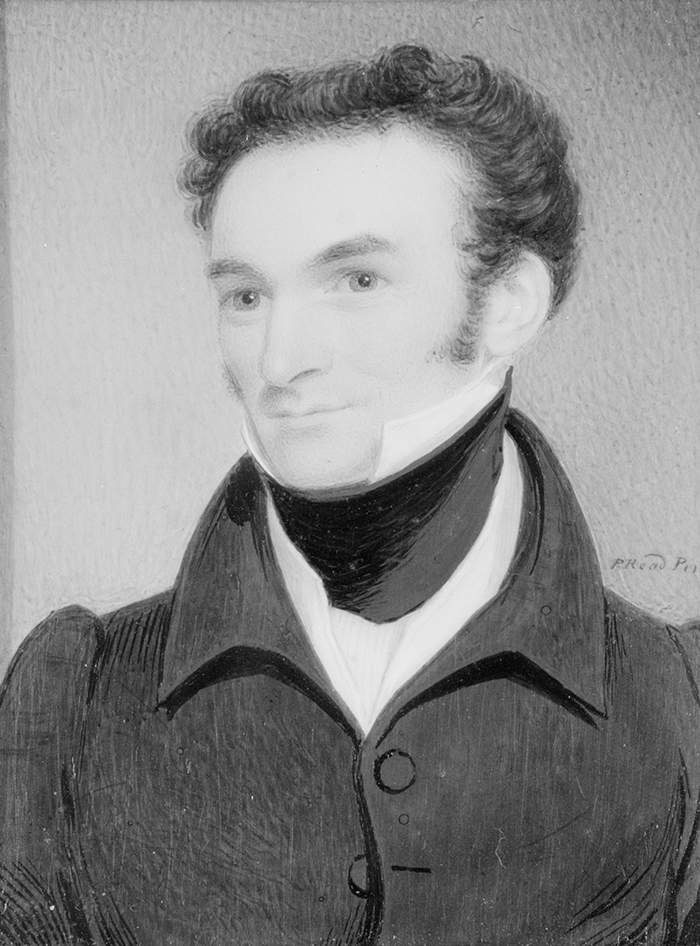

James Busby, the first British Resident in New Zealand, about 1860. In 1840, Busby helped draft the Treaty of Waitangi, adding the crucial promise that Māori would retain possession of their lands forests and fisheries.

PH-NEG-C1054

6 February 1840

THE TREATY IS SIGNED

British officials and more than 40 Māori chiefs sign the Treaty of Waitangi in the Bay of Islands. Copies are then sent around the country and signed by approximately 500 rangatira (leaders).

Under this founding agreement, New Zealand becomes a British colony and Māori become British subjects. However, Māori and Europeans have different understandings and expectations of the Treaty - particularly in relation to land.

Some Māori leaders believe the Treaty will enable more trade or help to limit inter-tribal fighting. Many do not sign, fearing they will lose their independence or power.

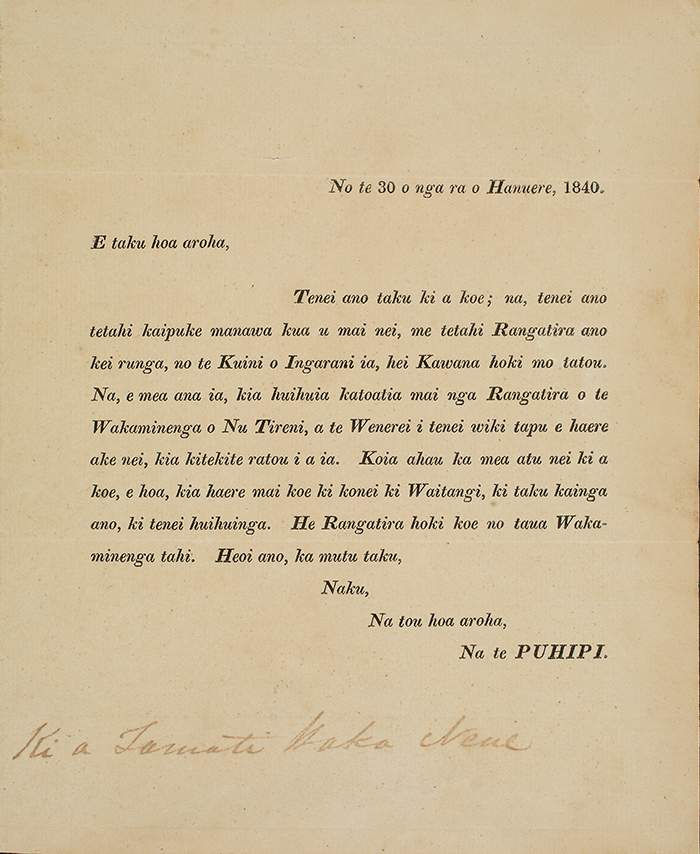

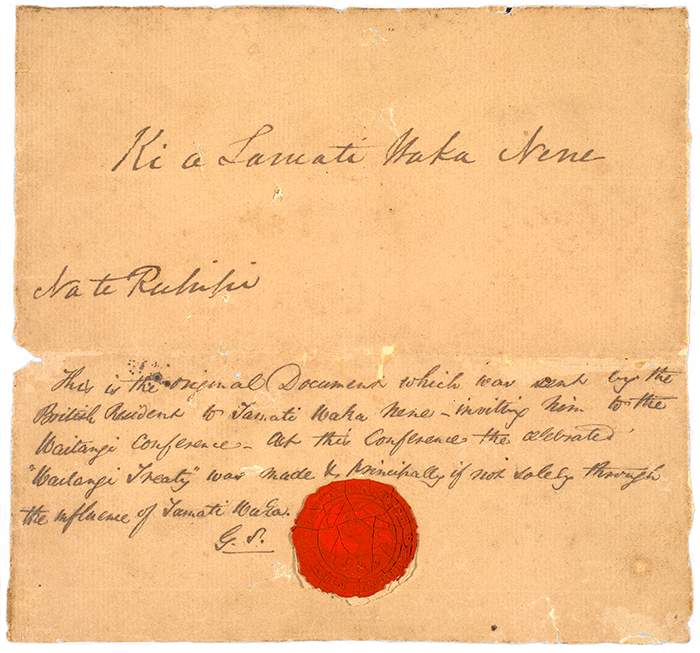

Invitation from James Busby to the chief Tāmati Wāka Nene, inviting him to the meeting at Waitangi in 1840. MS-93-116_01

Letter from James Busby to the chief Tāmati Wāka Nene, inviting him to the meeting at Waitangi in 1840. Wāka Nene played a crucial role in encouraging Māori to sign the Treaty, saying the British would protect them. MS-93-116

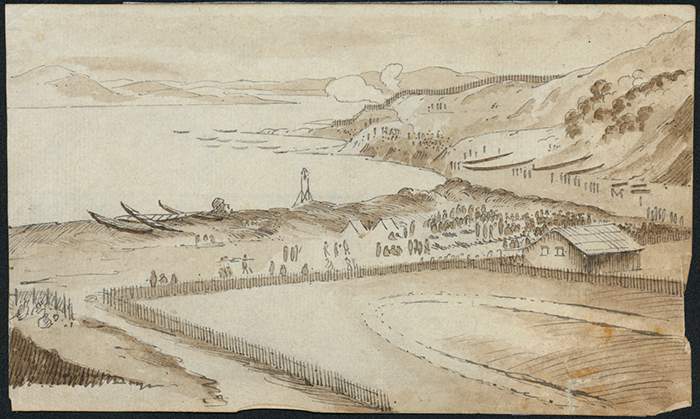

1840 Missionary station at 'Ourou' (Orua Bay) on the Manukau Harbour, about 1840. This sheltered bay is thought to be near the site of one of the Auckland region Treaty signings. Pen and wash on paper. PD-1963-8-23

1840

AUCKLAND CHANGES HANDS

The Auckland iwi Ngāti Whātua invite Governor Hobson to live in their region. Rangatira Te Kawau offers Hobson tuku rangatira (a chiefly gift) of access to land and resources of 8,000 acres - a vast area encompassing most of Auckland's suburbs today.

The concept of buying land outright is foreign to Māori, who believe they have entered a sharing arrangement. However, Hobson accepts what he understands to be a 'sale'. As a result, more than a third of the Tāmaki (Auckland) isthmus passes out of Māori hands.

Ngāti Whātua (Auckland region) chief Āpihai Te Kawau (left) and his nephew Tamahika Te Rēweti. GN671.1 ANG

1840s

FIRST SIGNS OF CONFLICT

In the 1840s, battles break out between Māori and Pākehā over sovereignty and land ownership. The conflicts, which intensify in the 1860s, become known as the New Zealand Wars.

The first Māori-Pākehā conflict after the Treaty signing is a bloody clash at Wairau, near modern-day Blenheim in the north-east of the South Island, in 1843.

In March 1845, Ngāpuhi warriors estroy the Northland settlement Kororareka (later named Russell). Other battles take place in Upper Hutt and Whanganui in the southern part of the North Island.

To find out more about the New Zealand Wars see www.teara.govt.nz or www.newzealandwars.co.nz.

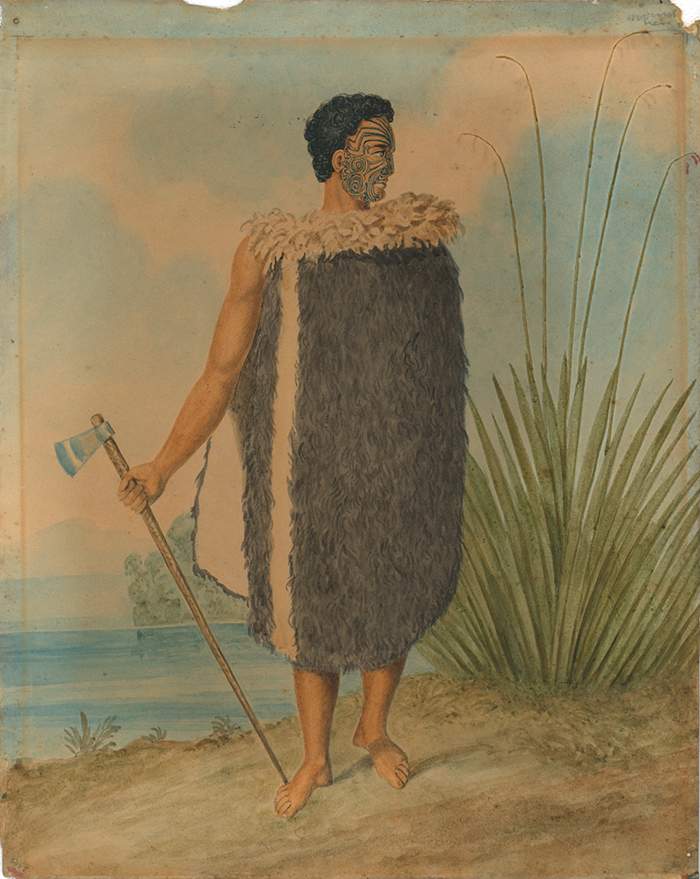

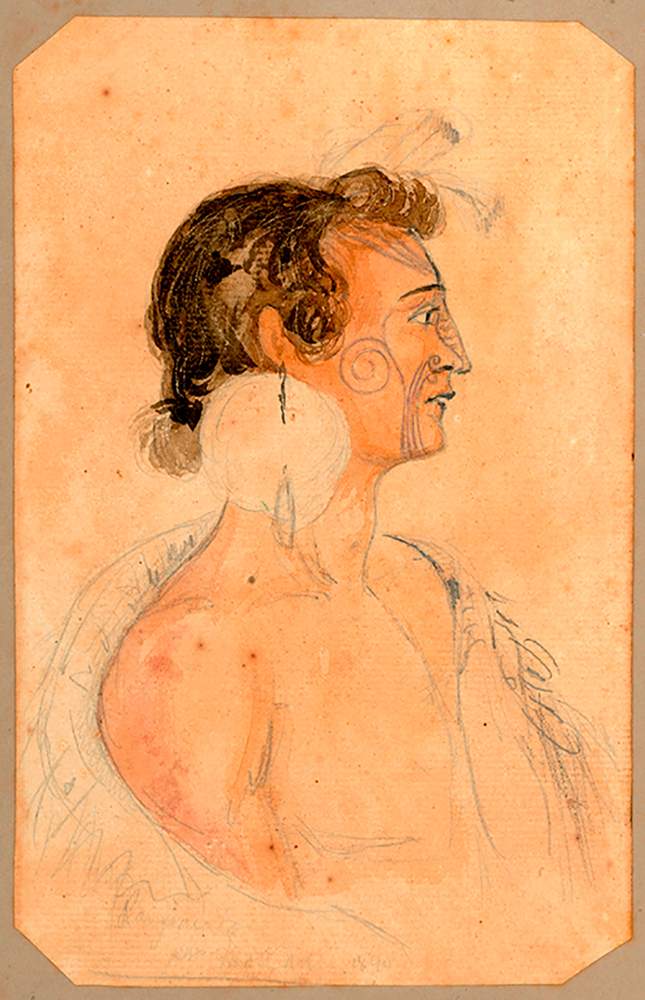

Te Rangihaeata, 1840. Te Rangihaeata was a Ngāti Toa leader who signed the Treaty. However when he learned that Māori would be permanently alienated from their land through sales to Europeans, he opposed it. Pencil and watercolour on paper. PD-1970-2-33

1846

GROWING PRESSURE

The Supreme Court states that Māori must officially register their land to prove ownership - customary use is not enough. Any land seen as not being actively cultivated by Māori is deemed 'waste land' that rightfully belongs to the Crown.

Settlers arrive from Britain in organised migration schemes, and some government agents use dubious practices to persuade Māori to sell. These include threatening military action, and buying from non-owners.

Too late, Māori begin to realise that what they are giving away in land transactions is absolute, sole ownership - a foreign concept.

1852

A KING FOR A QUEEN

The devout Christian Tamihana (or Katu), son of Te Rauparaha, travels with missionaries to England where he is presented to Queen Victoria. On his return, along with Wi Tako, Mātene Te WhiWhi and Wiremu Kingi, he begins promoting the idea of a Māori king as a source of national unity.

Tāmihana's aim is to limit land sales to Europeans so the two peoples can live peacefully side by side.

May 1854

THE FIRST PARLIAMENT

New Zealand's first parliament meets in a cramped building at Mechanics Bay, Auckland.

Under the New Zealand Constitution Act, Māori or Pākehā men who own land worth more than £50 are allowed to vote. Although enlightened for its time, this rule sidelines Māori as their land is mostly communally owned.

There are no Māori among the nation's MPs. It is not until 13 years later in 1867, that the first Māori MP is sworn in.

Mechanics Bay, Auckland. New Zealand's first parliament was established here in 1854. PH-ALB-88-p40-41

1858

THE FIRST MĀORI KING

The Waikato chief Pōtatau Te Wherowhero is declared the first King for Māori, ending a long search for a monarch.

It is hoped a king will help halt the loss of land, unite iwi (tribes), and give them more political power. Calls for a monarch had begun in the early 1850s, when growing numbers of European settlers and demand for land left Māori lacking political power. Mātene Te Whiwhi and Tāmihana Te Rauparaha spent years travelling around the North Island looking for a willing candidate, but most chiefs declined.

The Kīngitanga - or Māori monarchy - will become one of New Zealand's most enduring institutions.

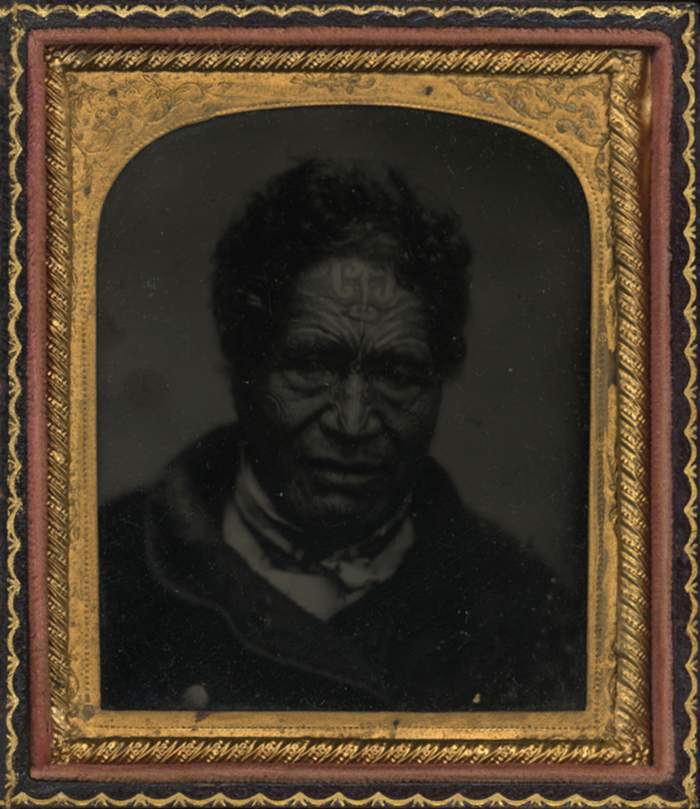

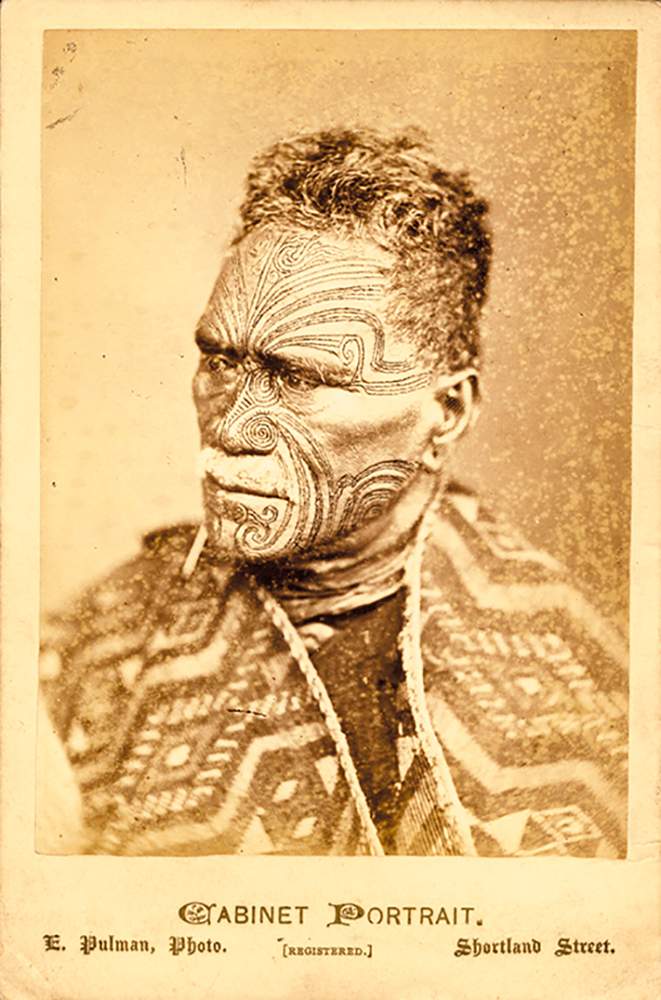

Tāwhiao, the second Māori king, 1882. The early part of Tāwhiao's 34-year reign was dominated by the Waikato War. His reign coincided with the most turbulent years of Māori-Pākehā conflict.

July 1860

THE KOHIMARAMA COVENANT

About 200 Māori meet at Kohimarama, Auckland, to discuss the Treaty of Waitangi and land.

The organiser, Governor Thomas Gore Browne, is keen to secure loyalty and draw attention away from the Kīngitanga (Māori King movement) and fighting in Taranaki. After much discussion, rangatira (Māori leaders) reaffirm the Treaty of Waitangi and pledge not to act against the British Queen's sovereignty, in the hope that this will reinstate their rights guaranteed by the Treaty of Waitangi. The pledge comes to be known as the Kohimarama Covenant.

The chiefs also request an annual conference, but this does not happen as the country moves into a decade of civil war.

Mission station at Kohimarama (Mission Bay) c1865. PH-ALB-88

1860s

A DECADE OF WAR

The 1860s are the peak of hostilities in the New Zealand Wars. Māori across the country refuse to give up their land, while the Crown tries to stamp out independence movements in Taranaki and Waikato.

Māori who oppose the Crown have about one million hectares of land confiscated.

Te Arawa Flying Column at Roto Kākahi, Rotorua district, 1870. This fighting force, loyal to the Crown, was formed to fight Te Kooti in central and eastern North Island. Albumen silver print. PH-ALB-86-p45-88

Plan of Gate Pā, Tauranga, 1864. At the battle of Gate Pā in 1864, Māori defeated British troops by using trench warfare. Illustration by Horatio Robley. PD-48-49

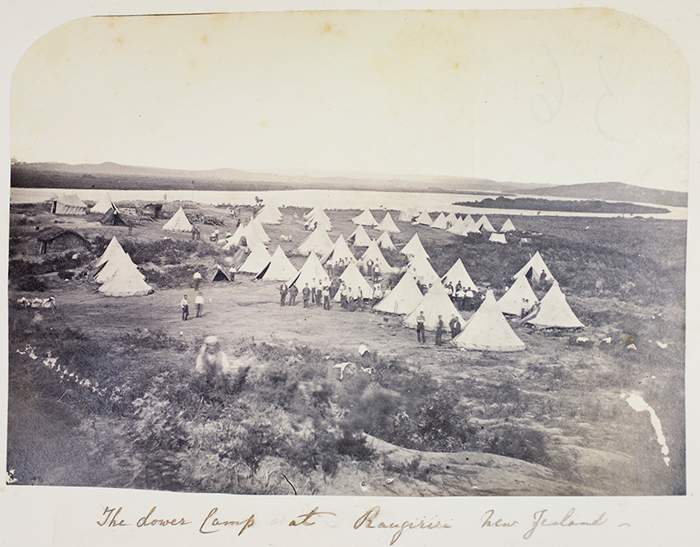

June 1863

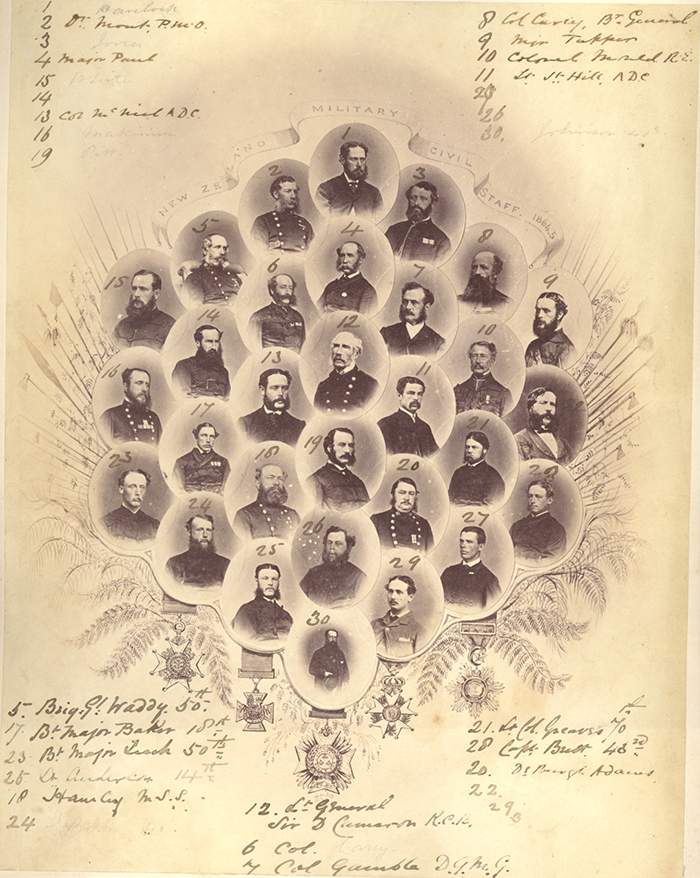

THE WAIKATO INVASION

British forces led by Lieutenant-General Duncan Cameron invade the fertile Waikato region south of Auckland. It is the first step in a crushing campaign that involves more than 18,000 troops and aims to put an end to the Kīngitanga (Māori king movement).

Governor George Grey sees the Kīngitanga as a threat to colonial authority. He also needs fertile land for the rising tide of immigrants. He uses rumours of a Māori attack on Auckland to convince his British masters to back the invasion, and vows to 'dig around' the Kīngitanga until it falls.

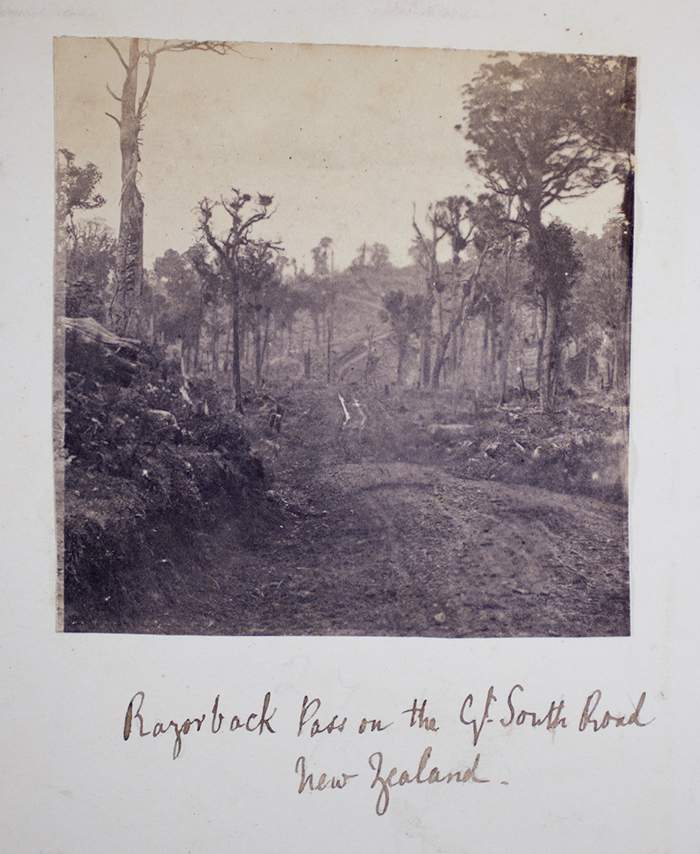

Auckland's Great South Road is built as a military supply route.

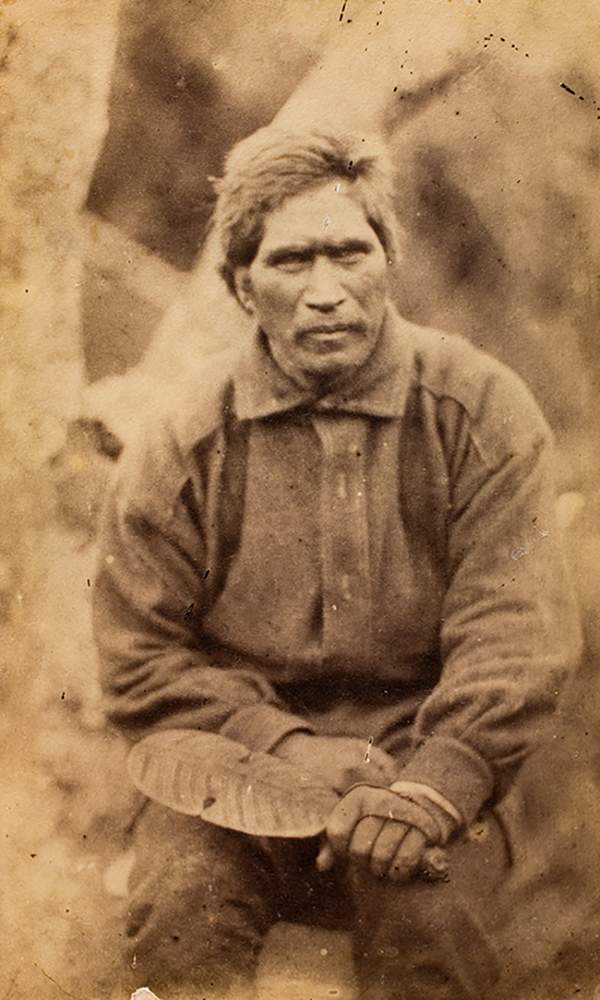

Ngāti Hauā chief Wiremu Tāmihana, about 1863. PH-ALB-89-p13-1

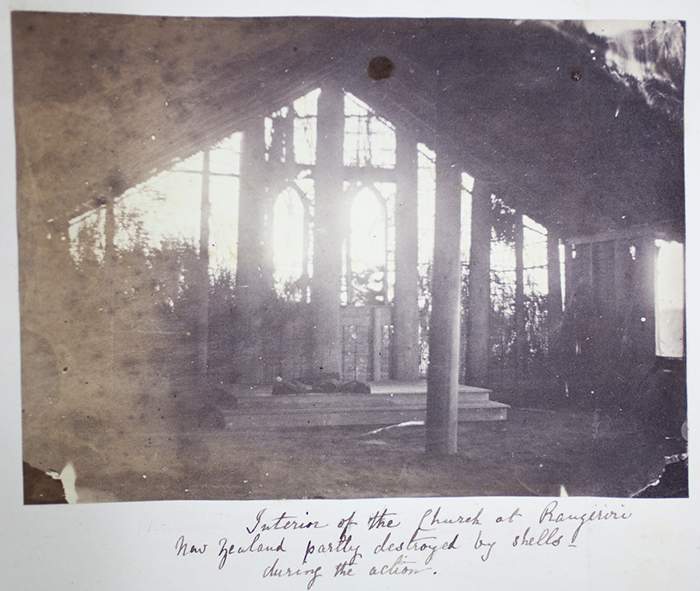

Interior of a church at Rangiriri, Waikato, c1870. Rangiriri was the key battle in the Waikato invasion. This church was partly destroyed by gunfire. Photograph by M Higginson. Album PH-ALB-510-p5

Rangiriri, Waikato region. PH-ALB-510-p6-3

Razorback Pass on the Gt. South Road, Bombay, Auckland. Photograph by M Higginson. Album PH-ALB-510-p5

1863

WITH US OR AGAINST US

The government, now at war, hastily passes the New Zealand Settlements Act. This allows the Crown to take land from any North Island Māori 'in rebellion against Her Majesty's authority' and paves the way for the large-scale European settlement of the North Island.

Some prominent Pākehā criticise the Settlements Act from the start. Sir William Martin, the former chief justice , argues that the result will be a 'brooding sense of wrong'.

Later, the law is changed so that small areas of land can be awarded to surrendered 'rebels'.

1877

A 'SIMPLE NULLITY'

The Chief Justice of the Supreme Court rules that the Treaty of Waitangi is a 'simple nullity' - worthless in the eyes of the law. Judge James Prendergast's statement is a low point for Treaty relations - influencing government decisions on Treaty issues for decades.

Prendergast makes his comments in a case involving a request for the return of Māori land and Porirua near Wellington. He rules that the courts cannot consider claims based on 'native' titles since the Treaty was signed between 'a civilised nation and a group of savages'. Many of his conclusions are overturned by the 1900s, but his attitude prevails in official responses to Māori land claims right up to the 1970s.

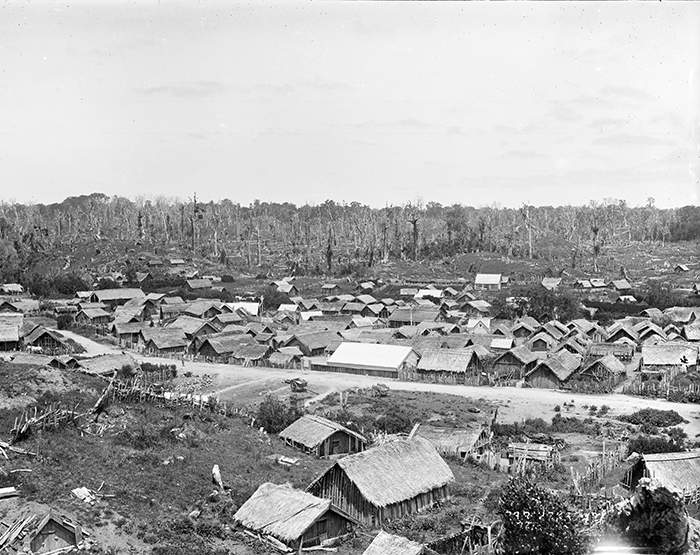

1881

THE ATTACK ON PARIHAKA

Government troops attack the pacifist Māori community of Parihaka, which was set up on confiscated land in the Taranaki region. About 1,600 people are expelled, and their homes destroyed.

The community's leaders, the prophets Te Whiti and Tohu, are arrested. Te Whiti had led peaceful protests against land confiscations, hoping to make Parihaka 'Israel' - a new kingdom for Māori - and reclaim their rangatiratanga (chieftainship) guaranteed by the Treaty.

1899

THE SOUTH AFRICAN WAR

New Zealand sends thousands of men to fight in the South African War (or 'Boer' War). It is the first time the country has sent troops overseas. Some Māori are eager to join them, and Premier Richard Seddon cites the Treaty as a reason for sending Māori as participants - as equal citizens.

Māori MP Wiremu Pere volunteers to lead a Māori contingent of more than 500 soldiers. But this is declined, as British government policy is not to use 'native' troops in wars between white groups.

About 200 Māori end up fighting with the New Zealand troops - most have Pākeha names.

Ngāpuhi nurses, Whangarei, 1901. These Māori nurses dressed in mock military uniforms and fundraised in support of the South African (Boer) War. PH-CNEG-C42329

NZ Premier Richard Seddon farewells troops soon to fight in the South African (Boer) War, 1899. PH-NEG-B667

1914

FROM ONE KING TO ANOTHER

The Māori King, Te Rata Mahuta, sails to London and makes a direct appeal to King George V over land grievances. The response from the British government is the same as it has been for decades: this is a matter for the New Zealand government to decide.

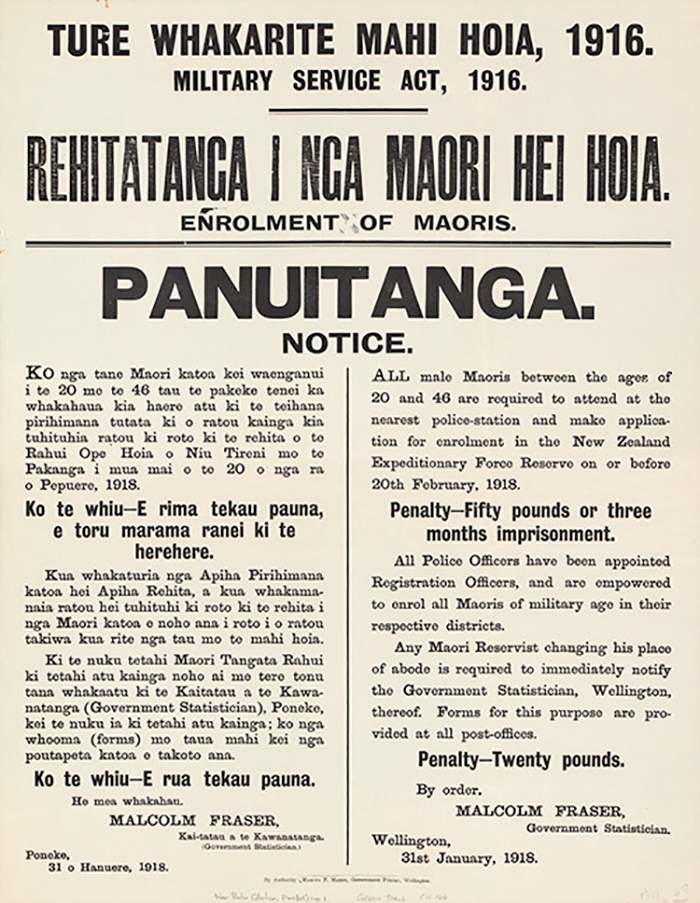

1914-18

WORLD WAR I

When World War I breaks out, Māori have mixed views about taking part. Some rush to sign up. But many from Taranaki and Waikato-Tainui refuse to fight for a Crown that confiscated their land in the 1860s. Some remember the words of King Tāwhiao, who had called for peace after the bloodshed of the New Zealand Wars - forbidding his people to take up arms again.

"The killing of men must stop: the destruction of land must stop. I shall bury my patu in the earth and it shall not rise again ... Waikato, lie down. Do not allow blood to flow from this time on."

When conscription is introduced in 1916, Waikato-Tainui are the only Māori forced to join the troops.

1915

LAND FOR RETURNED SOLDIERS

The government passes the Crown Discharged Soldiers Settlement Act - a law that allows it to gift land to returned soldiers for farming. Most is allocated to Pākehā soldiers, as it's assumed Māori veterans have tribal land available to them.

Some large parcels of confiscated Māori land are given to veterans via a ballot. More than 10,000 men are assisted onto the land by 1924.

Soldiers' resettlement form, 1917. Soldiers returning from World War One used this form to apply for land and vocational training. EPH-W1-28-7

1939-45

WORLD WAR II

Nearly 16,000 Māori enlist for service in World War II. The Māori Battalion becomes one of the most celebrated units in New Zealand military history. The remarkably high casualty rate is devastating for Māori communities across the country.

Many view the war as a positive step forward for race relations. Māori leader Āpirana Ngata stresses that Māori participation in World War I was the price of citizenship; after the Second World War it was clear that Māori had paid in full.

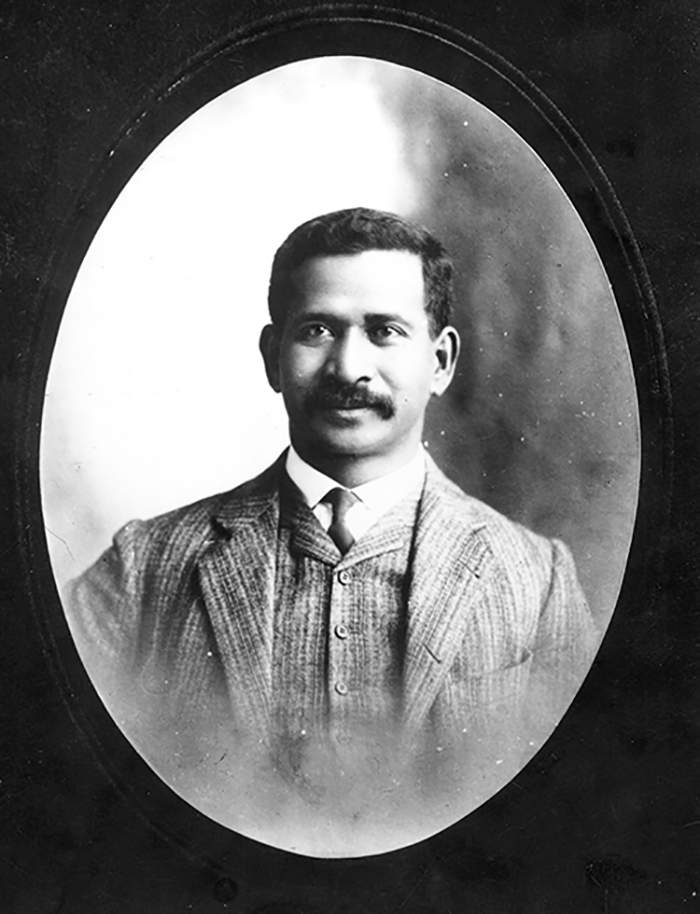

Māori leader Āpirana Ngata, early 1900s. Silver gelatin print. PH-RES-4922

Members of the 28th Māori Battalion in Italy c1945. PH-2009-1

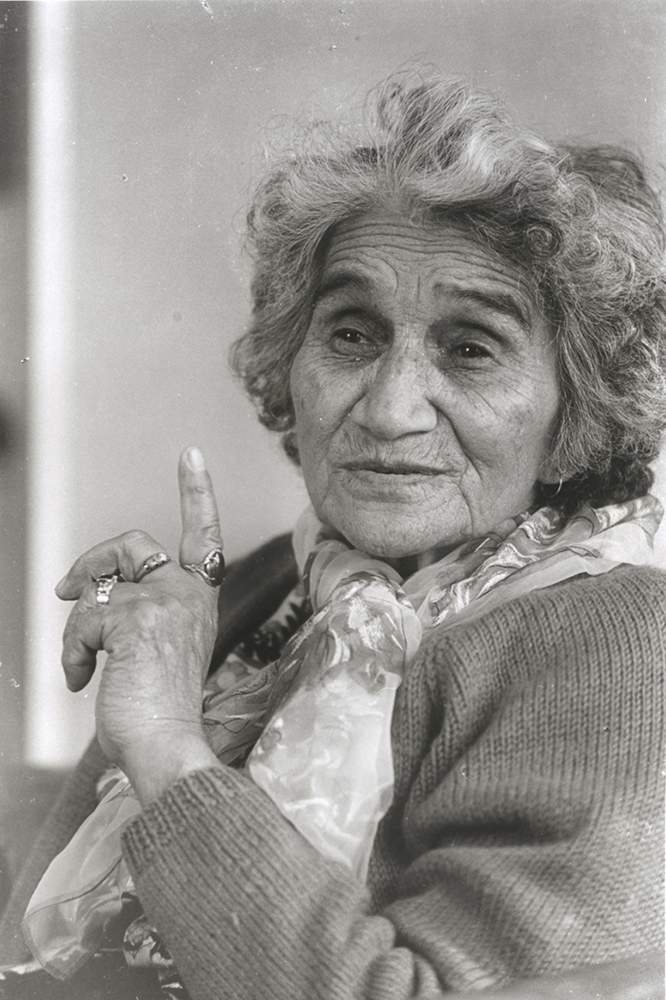

1975

THE LAND MARCH

Northland kuia (elder) Whina Cooper leads an 800-kilometre protest march in support of Māori land rights. The peaceful hīkoi travels from the Far North to parliament in Wellington, where thousands of people call for the government to honour the Treaty.

The 1970s usher in a new awareness of Treaty issues. Protests groups such as Ngā Tamatoa call for the teaching of Māori language and culture in schools, and call for the government to honour the Treaty.

A Māori language petition is delivered to Parliament. Ngā Tamatoa, supporters of the Māori language, take the 1972 petition to Parliament, led by a kaumatua. Te Ouenuku © Fairfax Media NZ / Auckland Star Collection

Dame Whina Cooper, 1975. Dame Whina's historic land-rights march from Northland to Wellington made a lasting impression on New Zealanders, regardless of race. Photograph by Robin Morrison. PH-1992-5-RM-N7-2

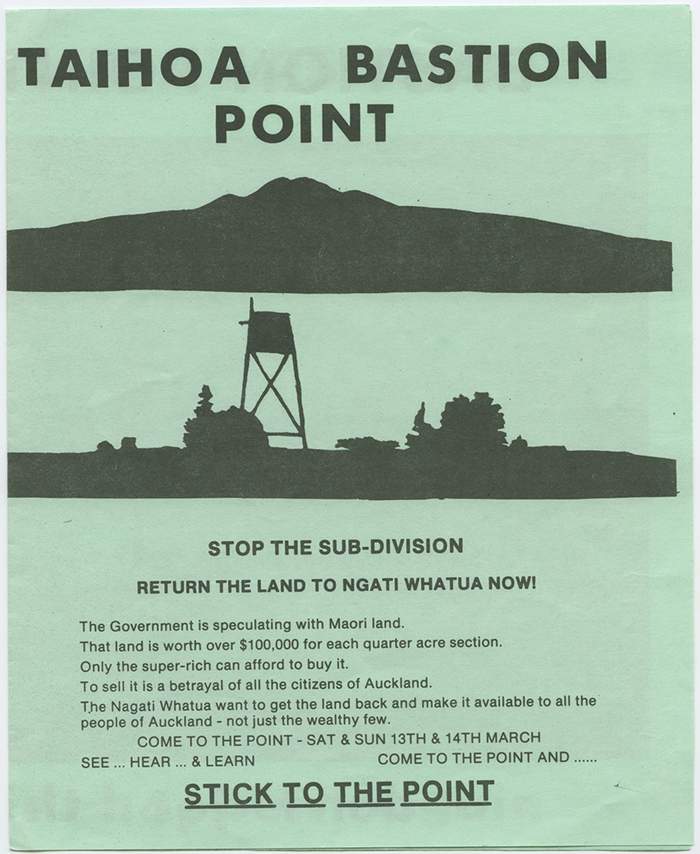

1977-78

BASTION POINT

A LANDMARK PROTEST

Members of the Auckland iwi (tribe) Ngāti Whātua occupy land at Bastion Point, Orākei, for 17 months. They are eventually evicted in the country's largest police operation up to that time. The Crown later admits the land had been unfairly acquired.

Bastion Point protest, 1978. Robin Morrison Collection. PH-NEG-RM-N10

Bastion Point protest, 1978. Robin Morrison Collection. PH-NEG-RM-N10

Bastion Point protest, 1978. Robin Morrison Collection. PH-NEG-RM-N10

Bastion Point poster, 1978. This poster calls for the return of land at Bastion Point to the Auckland tribe Ngāti Whātua. 'Taihoa' means to wait or be cautious. EPH-PRO-3-3

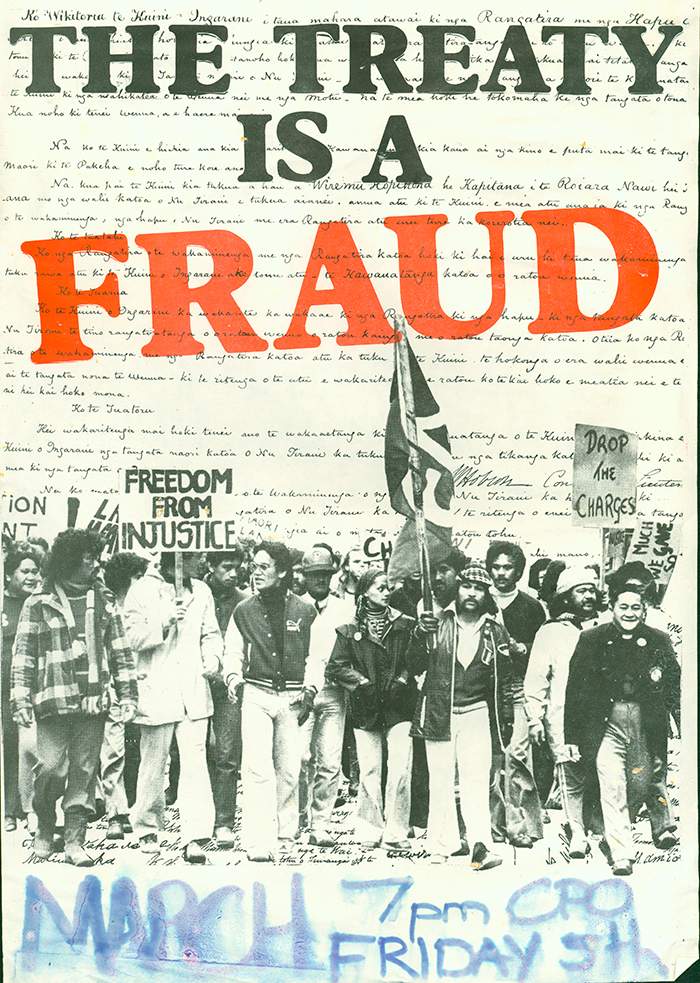

1985

HEALING THE PAST, BUILDING A FUTURE

The government sets up the Waitangi Tribunal to investigate Crown breaches of the Treaty. At first it only considers recent breaches. But in 1985, it starts hearing claims dating back to 1840.

Settlements usually include some land returns, compensation and apology from the Crown. Some New Zealanders complain that the processes unfairly benefits a few. Many others see it as a unique attempt to makes amends for for colonial injustices.

The settlement with Waikato-Tainui tribes includes a formal apology from Queen Elizabeth II. It is the first time the Crown has apologised to an indigenous people.

Treaty protest poster, 1978. This is one of many protest-march posters spanning 1975-1990 held by Auckland Museum. PT3-71

Tuaiwa Hautai "Eva" Rickard leads protestors across the bridge at Waitangi, on Waitangi day 1984. Photograph by Gil Hanly.

PH-2015-2-GH538-33

Protestors at Waitangi, 2014. Photograph by Gil Hanly. PH-2015-2

To learn more about this contemporary process and the Office of Treaty Settlements, visit www.tearawhiti.govt.nz

![Chart of New Zealand explored in 1769 and 1770 by Lieut. J. Cook, Commander of His Majesty's Bark Endeavour. Engraved by J. Bayly. [London], 1772. G9080 Chart of New Zealand explored in 1769 and 1770 by Lieut. J. Cook, Commander of His Majesty's Bark Endeavour. Engraved by J. Bayly. [London], 1772. G9080](./media/chart-of-nz-gg9080-700x_xqbqcnn-lr.jpg)